11 Oct 2016 Legal Time Limits on Egg Storage Creates New “Biological Time Clock”

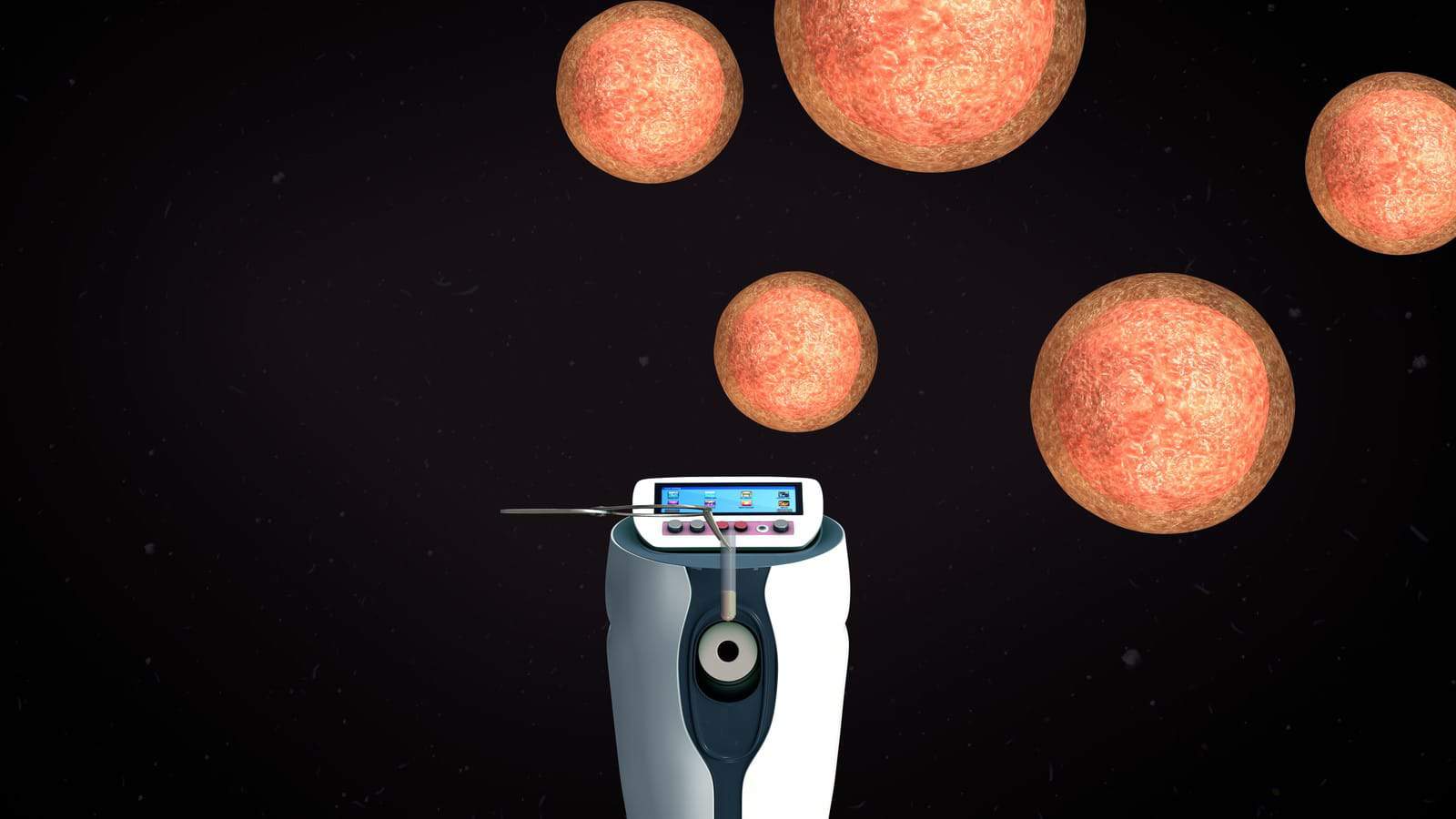

A new study by the London School of Economics argues that the U.K.’s statutory 10-year limit on storage of cryopreserved eggs or embryos has created a double standard and has, in a classic example of unintended consequences, replaced one kind of “biological timeclock” with another.

In many parts of the world the length of time frozen embryos or eggs may be stored is limited by law. In Sweden, for example, only unfertilized zygotes can be stored, and the storage period is limited to five years; in the U.K. the period for storage of frozen eggs or embryos is 10 years, whereas in the United States there are no legal limits on how long frozen eggs or embryos can be stored.

Many of the legal limitations were enacted decades ago when there was little research available on the “shelf life” and potential safety concerns with frozen eggs and embryos. Today, however, we know that cryopreserved eggs and embryos can remain viable and result in health live births far beyond 10 years.

Donna Dowling-Lacey, M.S., co-authored a 2011 case study of a successful live birth to a 42-year old woman, using a donated embryo that had been frozen and stored for nearly 20 years. As the article describes, the donated embryos were the result of an IVF cycle performed by an infertile couple using their own gametes in January 1990. The embryo donor couple had a healthy baby boy in 1990, following the transfer of cryopreserved embryos using their own gametes. The donor mother was 34 at the time the embryos were fertilized.

In 1993, the couple signed a disposition consent form allowing five remaining frozen embryos to be anonymously donated to a qualified recipient. In 2009 a 42-year-old recipient was matched to the donated embryos, two of which remained viable after thawing. The recipient gave birth to a healthy baby boy in May 2010. Her pregnancy was the first resulting from implantation of a human embryo that had been frozen for that length of time, nearly 20 years. As the case study noted, “animal models have already shown that extended cryostorage does not affect embryo survival or healthy deliveries.”

Embryo and/or egg viability is only one motivation for jurisdictions in imposing time limits on cryopreservation and storage of embryos. Other considerations, such as legal complications related to inheritance, the legal and moral obligations of fertility clinics to preserve embryos, and even a shortage of storage space, have been cited.

In the U.K., The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 was updated in 2009 to provide women facing premature infertility, such as early menopause, to store frozen eggs for an extended period of time, up to 55 years. But no such consideration was given to women who might choose to store their frozen eggs for longer periods due to natural age-related declines in fertility. This imposed a double standard, writes Professor Emily Jackson of the London School of Economics Department of Law, whose paper, “‘Social’ egg freezing and the UK's statutory storage time limits,” was published recently in the Journal of Medical Ethics—one set of rules for women who might opt for cryopreservation of eggs for health reasons such as cancer treatment or a hysterectomy, another set for women who might need to delay procreation for career, financial or relationship reasons. The law also set a different standard for men, who are allowed to cryopreserve their sperm into old age.

The rule may also result in a number of unintended behavioral consequences. Assisted reproduction can be a way for women to avoid the pressure of the so-called “biological time clock,” allowing them to preserve their eggs at the height of their fertility but postpone gestation until later in life. But an imposed time limit on storage may push a woman to use frozen eggs before the legal clock runs out, creating a new version of the biological time clock. A woman may feel compelled her to use donor sperm if she’s still looking for “Mr. Right,” or may push her and a partner to procreate even if the family is not financially prepared for her to take time off from her career.

Likewise, as the School of Economics study points out, even though eggs frozen when a woman is in her prime years of fertility—30 and younger—have a greater chance of viability, she may wait to freeze her eggs until she is in her mid-thirties in order to have the option to conceive in her 40s.

The mandating of artificial legal limits on how long frozen eggs or embryos can be stored seems arbitrary and unfairly applied and undoubtedly forces people into the unnecessarily harsh choice between their dreams of having a genetically related child or rushing to start a family at an inopportune time. “By mandating the destruction of a woman's eggs during her reproductive lifespan, unless she happens to be prematurely infertile, the rules are illogical and their effects perverse,” Jackson writes.

She claims the storage time limits have been retained so that clinics are not obliged to store eggs indefinitely. “But this could easily be achieved by allowing for rolling time-limited extensions, as happens for women who are prematurely infertile,” she continues. More research is needed, she says, on the impact of a 10-year cap on egg storage on women’s behavior and decisions about whether and when to freeze their eggs.