06 Nov 2017 What to Do With Abandoned Embryos

The problem began decades ago, in the late 1970s, as soon as the first babies created via the then-new technology of in vitro fertilization began to be born. It drew little notice for many years, growing slowly and steadily as a side-effect of the revolution in fertility treatment and reproductive health. But as the technology improved, as more and more people turned to assisted reproduction technology, and as best practices for embryo implantation evolved, the problem mushroomed: What to do about the by now hundreds of thousands of unused and abandoned embryos, created through IVF and cryopreserved, that crowd the storage facilities of fertility clinics all over the United States?

In my role as chair of the American Bar Association’s Family Law Section Committee on Assisted Reproduction, I had the privilege of speaking on this topic as part of a roundtable discussion at the 2017 American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) Scientific Congress & Expo on Nov. 1. Among those participating in the roundtable were reproductive endocrinologist Dr. Craig R. Sweet; attorney Tim Schlesinger, who represented the winning party in a Missouri Supreme Court case over disposition of frozen embryos (McQueen v. Gadberry—see our article); Amy S. Erickson Hagen, quality assurance officer for long-term U.S. cryopreservation/storage company Reprotech; leading Texas ART attorney Greg Stern; Christina Miller, Chair of the ABA Family Law Section Committee on Alternative Families; and Liesl Nel-Themaat, Ph.D., andrology team leader and endocrinology lab supervisor at the University of Colorado’s Advanced Reproductive Medicine program.

A single round of IVF treatment can result in the creation of numerous embryos. In the early years of IVF practice, fertility physicians typically would implant multiple embryos in order to increase the chances pregnancy would occur. But the result of such multiple implantations was often multiple births, which increase risks both to the babies and the birth mothers. Even then, there were often many more embryos created than were used in the IVF procedure.

Over time, as the technology improved, doctors were able to implant fewer embryos with good success rates, and by 1998 the standard practice was to implant no more than two or three, choosing those that appeared strongest and most viable. The number of “left-over” embryos grew.

The issue has become highly politicized by conservative lawmakers and advocates who have attempted to enact “personhood” laws that define embryos (including frozen embryos) as “persons.” The advent of embryonic stem cell research drew even more attention to the ethical issue of using embryos for medical research.

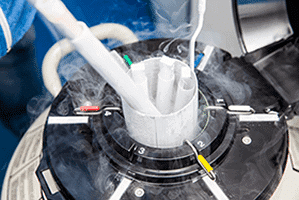

In most cases, IVF patients are required to sign an agreement outlining the disposition of frozen embryos in the event of patient death, divorce or separation. The patient usually has the choice of discarding or destroying the embryos, donating them for use by another infertile patient, or donating them for medical research. Typically, the IVF clinic will store frozen, unused embryos for a period of time in the event the client wants to have more children at a later time, or the embryos may be transferred to a cryopreservation facility for long-term storage. In either case, the client pays a storage fee.

But sometimes the storage bills go unpaid. Sometimes patients move or fail to respond to repeated attempts to contact them. Today there are an estimated 600,000 to 4 million frozen embryos stored in the United States that are abandoned or unclaimed, representing an enormous burden for clinics and storage facilities.

At a traditional storage rental facility, the customer who repeatedly failed to pay storage fees would find his belongings locked up and auctioned off or thrown out into the street. The facilities where frozen embryos are stored have no such easy recourse—ethical and legal issues abound. Reputable clinics and storage facilities go to great lengths to ensure that patient wishes are honored, making repeated attempts to contact embryo owners and often continuing to store embryos despite decades of unpaid bills rather than destroying them without permission.

There are no federal regulations or statutes governing the disposition of frozen embryos created through ART. State courts follow a patchwork of judicial and legislative remedies. Laws directly related to embryo disposition are few and often lumped in with disposition of genetic material or medical waste. In some cases, state laws governing embryos are inconsistent with other laws governing personhood, wrongful death, homicide and stem cell research.

Even California, generally progressive in regard to ART law, remains largely silent when it comes to providing a framework for attorneys and the courts to resolve questions of embryo abandonment and dissolution.

The California Health and Safety Code Section 125315 requires reproductive healthcare providers to give ART participants a consent form with options for disposition of the reproductive material upon the occurrence of certain contingencies. The California Penal Code 367g makes it a felony to use or implant sperm, eggs or embryos except as expressly provided in a signed writing by the provider of the genetic material. Taken together, these statutes arguably may suggest that control and decision-making authority over reproductive material belong to each person individually.

As in most areas of ART law, developing a set of best practices for abandoned embryo disposition is still a work in progress. The issue of abandoned embryos will continue to challenge clinics and cryopreservation facilities until the law catches up to the technology. For the time being, providers are advised to check state law to ensure consent forms are in compliance. For any use other than originally authorized by the patient, require an updated, signed consent, and be sure it is notarized to ensure the patient’s wishes are honored in the event of death or divorce. Last but not least, clinics should establish a written protocol for contacting patients and determining whether embryos are indeed abandoned. The protocol itself will serve to let patients know the consequences of failure to pay storage or loss of contact.

IVF patients and intended parents also bear a responsibility to be as informed as possible about the IVF process, to carefully consider all potential outcomes when making decisions about unused embryos, and to live up to their contractual commitments to their clinic or storage facility. Anecdotal reports indicate some owners of unused embryos cut off contact with clinics or storage facilities out of guilt: They want neither to have additional children nor to continue paying storage fees, but they don't want to make the call to have the embryos destroyed. Some assume the embryos would be destroyed as soon as they stopped making payments, apparently oblivious to the dilemma they have created for the providers. After all, reproductive health care providers, cryopreservation and storage companies, and patients all have the same goal: fewer abandoned embryos.