21 Feb 2023 Disparities Persist in Fertility Treatment for Black Intended Parents

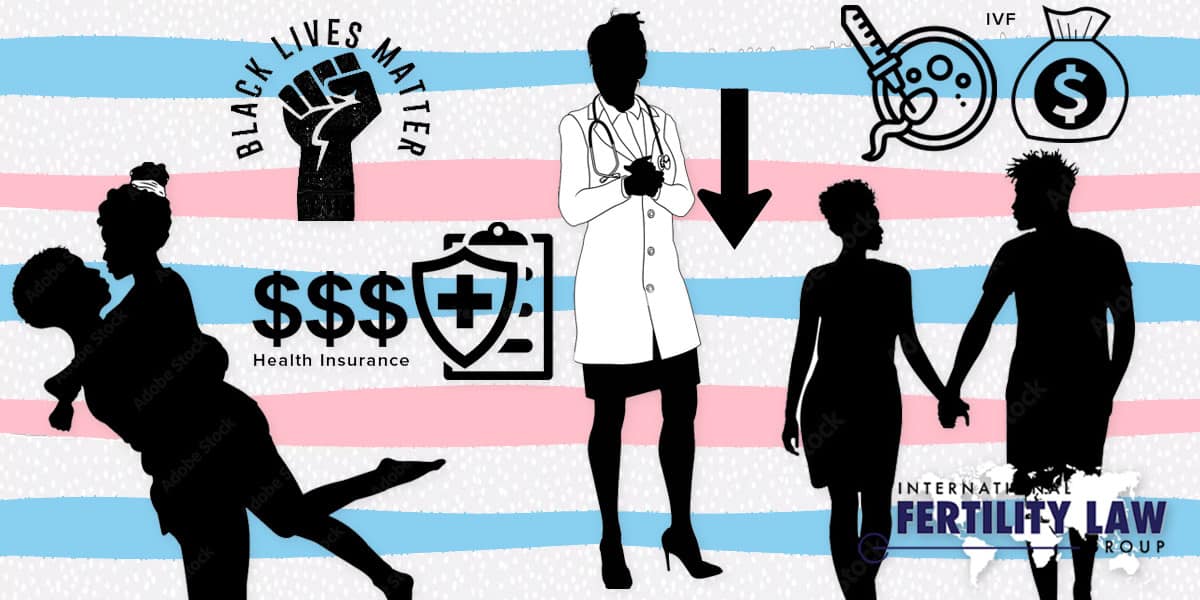

As America continues to celebrate and highlight achievements in the Black community for Black History Month, we at IFLG have taken the opportunity to highlight disparities the Black Community faces when it comes to dealing with infertility. Black intended parents still have a higher hill to climb compared to white intended parents in order to fulfill their dreams of parenthood.

As we reported earlier this month, white women between the ages of 25 and 44 are twice as likely to seek out fertility treatments earlier compared to only 8 percent of Black women who seek out treatment during child-bearing years. Black women also suffer from uterine health issues more frequently than white women on average and face a persistent myth of being hyper-fertile, which has led to a silent shame when discussions about infertility issues arise in the Black community. As a result, some Black women don’t feel as though they can talk about their infertility struggles or seek help.

These ongoing disparities, combined with limited state-mandated insurance coverage for infertility care and the high cost of fertility treatments, have resulted in an incredibly high percentage of the minority population left without help and reasonable access to assisted reproductive technologies.

According to RESOLVE, 20 States have passed fertility insurance coverage laws with 14 of those states covering IVF and 12 of them covering fertility preservation for medically induced infertility. However, rules vary from state to state, and Forbes states, “small employers (often defined as companies with 50 or fewer employees) and self-insured employers (companies that pay claims out of their own funds rather than using an insurance company) are often exempt from these laws.” Even with some states covering fertility treatments, Lynae Brayboy, M.D., FACOG, an African American ob-gyn specializing in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, tells Glamour, “There is a higher proportion of women of color who use federal insurance coverage or Medicaid. Medicaid has absolutely no coverage for infertility.” In 2018, the AMA Journal of Ethics stated that 34.7 million adults were enrolled in Medicaid, and federal civil service employees working for the US government also had no insurance coverage for infertility treatment.

High Costs Create Barriers to Fertility Treatment

Michell Bratcher Goodwin, a professor at the University of California Irvine School of Law Center and founding director of the Center for Biotechnology & Global Health Policy, tells Parents.com, “IVF costs are deeply prohibitive generally. The high costs are particularly difficult for families of color and single individuals who disproportionately lack intergenerational wealth. Where others who want to use IVF-related services may be able to access financial reserves--either their own or from family members--those types of options may be less available to families of color.”

The average cost of a round of IVF is over $12,000, which does not include other costs for genetic testing, time off work to undergo treatment, or yearly fees to store excess embryos in cryobanks, which can often exceed $1,000 annually. In total, the final cost for one round of IVF can be well over $15,000, and with many intended parents requiring more than one round of IVF to become pregnant, the dream of becoming a parent becomes even more unattainable.

Lack of insurance also plays a role in access to ART. Shaylene Costa, a doula and a Black mother of two who experienced more than a five-year journey with infertility before giving birth to her daughter, tells Glamour, “A lot of people talk about IVF and going to specialists, but that was not on the table for us, because we had no insurance. We were paying out of pocket for all of the treatments and blood tests, which meant that we ate ramen noodles instead of good food.” Data from the Census Bureau shows the median income for white households in 2020 was $74,912 compared to $45,870 for Black households. The disparity in income combined with the lack of generational wealth due to systemic racism only heightens the need for more legislation to prioritize inequities in reproductive care.

Goodwin goes on to say in Parents.com, “The desire to parent does not have a color line, and Black parents, for example, would be just as likely to seek medical assistance to achieve pregnancy as their white counterparts. That said, if assisted reproductive technologies are outside of reach because of economic constraints then Black families may be less likely to have meaningful access.”

Diversity Needed Among Reproductive Medical Professionals

Not only do disparities continue to exist with insurance coverage and the affordability of IVF costs, but they also exist in the lack of diverse backgrounds in the medical community.

According to a study at UCLA, the proportion of Black physicians in the U.S. has only increased by 4% in 120 years. Dr. Dan Ly, an assistant professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and author of the study, states, “These findings demonstrate how slow progress has been, and how far and fast we have to go if we care about the diversity of the physician workforce and the health benefits such diversity brings to the patients, particularly minority patients.”

Kimberly Wilson, a Black woman who suffered from fibroids and had been in and out of the hospital with complications, tells NBC News she had trouble finding a doctor who understood her cultural and mental health needs. The majority of doctors she saw were white men who advised her that her only treatment option for her fibroids would be a hysterectomy which would take away any chance she had of having any children. Wilson says that a referral from a friend led her to a Black ob-gyn at Johns Hopkins University who recommended an abdominal myomectomy that would preserve her uterus while still removing most of her fibroids and ultimately preserving her chance at having children one day.

Although thrilled with her outcome, Kimberly goes on to tell NBC News, “I was frustrated by my experience and having to travel so far just to find a culturally competent physician.” She believes she had a better experience because her doctor was a Black woman.

As a result of her experience, Wilson created HUEDCO, a digital health equity company that creates inclusive healthcare for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities by connecting them to medical professionals of color and offering research-based courses designed to equip healthcare professionals with the ability to remain open to each patient’s cultural background, values and traditions and how they impact a patient’s care.

Increasing the number of providers from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds and providing training against bias is essential in order to correct some of these long-standing disparities plaguing the Black community when it comes to reproductive health. Research shows that sharing a racial or cultural background with a patient’s physician can lead to higher patient satisfaction and health outcomes according to Parents.com. The need for more diverse medical professionals is evident, and the US has a duty to grow and diversify its medical workforce to not only root out systemic racism in the field but to be at the forefront of inclusion and equity for all humans no matter the color or socioeconomic status.

Intended Black parents have just as much desire as intended white parents to fulfill their dreams of parenthood but are more likely to face insurmountable obstacles preventing access to reproductive healthcare, including the lack of diversity in medical professionals. The human want and need to create a family transcends race and culture. Equal and comfortable access to reproductive health services and assisted reproductive technology should be a basic human right, free from judgement or financial barriers.