26 Aug 2019 Uniform Laws Needed to Regulate Abandoned Embryos

Over the past few decades, technological advances have made the miracle of reproduction and parenthood accessible to thousands of people who in an earlier time would have remained childless—people with genetic conditions, injuries or illnesses that result in infertility, people who are unpartnered or unmarried, and LGBTQ people. But, as so often happens in our human ecosystem, the growing number of people who benefit from assisted reproductive technology has resulted in an unintended consequence: a growing number of frozen (cryopreserved), unused, and, for all intents and purposes, abandoned embryos, many left to exist indefinitely in a frozen no-man’s-land of legal uncertainty and unclear liability.

As we first wrote about this issue in 2017, the root of the problem lies, partially at least, in the amazing advances in assisted reproductive technology. In the early days of vitro fertilization and embryo implantation, when successful outcomes were less certain, IVF doctors would typically implant multiple fresh embryos, newly fertilized in the lab, in hopes of achieving one successful pregnancy and birth, as CBS News reported earlier this year. Often, in another one of those unintended consequences, twins or multiple births resulted.

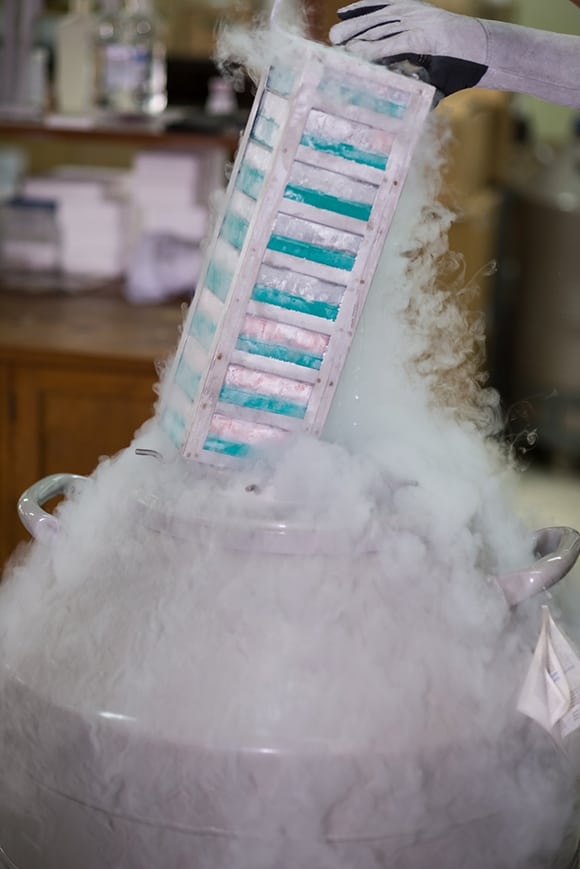

As cryopreservation technology improved, best practices in IVF evolved as well. “Now, couples usually freeze many embryos, test for health problems and transfer the most viable one at a time to avoid multiple births. That often means leftovers once the desired family is complete,” CBS News reported.

The success and growing reliability of advanced cryopreservation techniques opened new reproductive horizons for lots of people who otherwise could never have dreamed of having biologically related children. Young cancer patients undertaking invasive radiation or chemotherapies now had the option to freeze eggs or sperm years in hopes of procreating in a cancer-free adulthood, as did combat soldiers and others facing dangerous missions and career-focused individuals looking to put family-building off to a later time in life.

Advanced cryopreservation also had other exciting benefits. Infertile individuals or couples who succeeded in producing multiple viable embryos now could “bank” some for a future when they may or may not desire to have more children, without undergoing the sometimes arduous and costly cycle of egg extraction and fertilization again.

It is those “leftovers” that pose an a rapidly growing and seemingly intractable problem for the fertility industry.

These cryopreserved embryos, which might or might not be used in the future, and which might or might not result in successful pregnancy and birth if they were used, created a whole new set of legal issues, unimagined 30 years ago. Who has the right to decide whether frozen, unused embryos may be used or destroyed? IVF clinics began requiring intended parents, either at the onset of treatment or before viable embryos were stored, to sign medical consent forms with statements addressing future disposition of remaining embryos. Typically, these consent forms state how remaining embryos will be disposed of in the event the intended parents separate or divorce or in the event of the death of one or both parents. Typically, parents must choose among four options: to store embryos—for a fee, either at the clinic or an outside storage facility; to destroy them; to donate them to third persons for purposes of procreation; or to donate them for scientific research or training.

The now-standard use of such embryo disposition consent forms has helped a lot in avoiding conflicts between intended parents and, when that’s not possible, in helping courts determine the original intent of intended parents when existing embryos become caught up in a divorce matter.

But despite the widespread use of embryo disposition consent forms at IVF clinics, the problem of abandoned, unused frozen embryos has mushroomed. As we reported in 2017, no one is sure how many embryos are in storage in the United States—clinics and storages facilities are not required to report those numbers—but estimates range from hundreds of thousands to several million. The estimated portion of those that are “abandoned”—i.e., where storage fees are unpaid, and the owners cannot be contacted after reasonable measures to do so—ranges from 1 percent to as high as 18 percent at some clinics, according to the CBS report.

This burgeoning population of frozen embryos has spawned a whole new industry, as high-tech companies such as Reprotech ramp up long-term storage solutions for over-capacity clinics and intended parents who want to keep future options open.

This widespread abandonment presents IVF clinics, cryopreservation facilities and fertility doctors with a lose-lose decision: Discard abandoned embryos (after a set stated amount of time and after reasonable efforts at contact), risking the grief and anger of bereaved intended parents and negative publicity; or continue storing abandoned embryos, unreimbursed, for eternity—or until embryos are no longer viable.

Cryopreserved embryos have proven amazingly resilient; indeed, we reported about one case in which an embryo frozen for more than 20 years, donated to a 42-year-old woman, resulted in a healthy birth. The CBS story reports on a live birth resulting from implantation of a 24-year-old embryo. Scientists speculate that embryos stored in precisely controlled conditions might remain viable for decades. A 1980s study on mouse embryos indicated they could remain viable for a simulated 2,000 years.

There are myriad reasons why intended parents abandon the embryos that at one time were important enough for them to undergo invasive, time-consuming and expensive procedures to create. Arguably no areas of human life are more fraught with existential emotion than relationships, procreation and parenthood.

Most intended parents have good intentions; at the time they sign the disposition agreement, it sounds perfectly reasonable that, should they decide not to use remaining embryos within X number of years, the embryos can be discarded or donated. But then a beautiful child or two is born, created from embryos from that same frozen batch, and suddenly discarding the remainders in five years, or donating them to another family one doesn’t even know, doesn’t feel right anymore.

Cost also plays a role. Storage costs range from a few hundred dollars to more than $1,000 a year, depending on the facility.

Among these and other reasons embryos might be abandoned, couples break up, families relocate, and sometimes they “forget” to leave a forwarding address. Anecdotally, the underlying reasons are often more emotional. Destruction of embryos created during a loving relationship gone south can trigger feelings of grief and loss. Discarding embryos can mean discarding one’s only chance of having more children in the future. Sometimes, faced with such wrenching choices, intended parents simply avoid them, leaving fertility professionals to make the call.

In some countries the length of time frozen embryos can be stored is limited by law, relieving facilities of the burden of the decision. In UK, for example, as we wrote earlier, embryos may be stored for a maximum of 10 years for purposes of delaying reproduction. In Sweden, only unfertilized zygotes (eggs or sperm) may be stored, for a maximum of five years. As reported by NBC News earlier this month, Germany and Italy limit the number of embryos that can be created and implanted at one time.

In the United States, there is no legal time limit on storage of eggs, sperm or embryos, and when intended parents renege on their dispositive responsibilities, clinics are left with a growing and increasingly risky problem.

In the absence of legal guidance, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) Ethics Committee has attempted to provide ethical guidelines for clinics and storage facilities.

At present, the law does not give clear guidance on when it is lawful to discard abandoned embryos, although it is reasonable to consider that the law will treat the embryos, after a certain passage of time, as abandoned. In the face of legal uncertainty, some programs might prefer to continue storage of abandoned embryos indefinitely. Other programs will find the risk of liability to be acceptable and dispose of embryos after a lengthy passage of time and unsuccessful efforts to contact those with dispositional control. As an ethical matter, a program should be free to dispose of embryos after a passage of time and unavailability of a responsible individual or couple that reasonably indicates that the couple has abandoned the embryos. A program's willingness to store embryos does not imply an ethical obligation to store them indefinitely. An individual who, or couple that, has not given written instruction for disposition, has not been in contact with the program for a substantial period of time, has not provided current contact information, and who cannot be located after reasonable attempts by the program and facility, cannot reasonably claim an ethical violation on the part of the program or facility that treats the embryos as abandoned and disposes of them. This statement notwithstanding, the Committee recognizes the legal uncertainty surrounding a determination of abandonment and does not provide legal advice in this regard for the program or facility.

While it is easy to understand and empathize with intended parents faced with the difficult decision of what to do with unused embryos, it’s also important to acknowledge that the medical professionals who work so hard to create new life, to fulfill the dreams of would-be parents, are human, too. Most are passionately devoted to their specialty and to making parenthood possible for their patients. For many, the unfair burden of being forced to unilaterally decide whether to preserve or destroy the products of their labor and expertise is too heavy. The obvious solution is to support clinics and cryopreservation facilities with long-overdue legislation, regulating and standardizing the rules around abandonment and storage requirements, so that the burden of decision—and the risk of legal liability—is lifted.