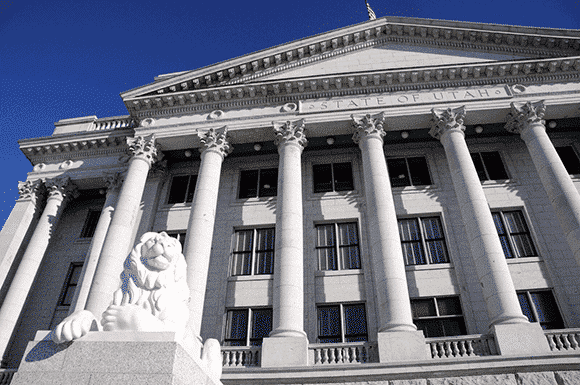

14 Aug 2019 Utah Supreme Court Strikes Statute Denying Surrogacy for Gay Dads

“This appeal comes to us unopposed,” reads the first sentence of the Utah State Supreme Court’s August 1 decision striking down a statute that denied same-sex married couples equal rights to participate in surrogacy agreements automatically afforded to married heterosexual couples. In a rare sign of growing acceptance of reproductive rights—however grudging—in an historically conservative stronghold, the state of Utah joined the petitioners in an amicus brief.

Utah law allows gestational surrogacy under certain narrow circumstances. In order for a gestational surrogacy agreement to be valid and enforceable, the parties to the gestational surrogacy agreement must be approved by a district court.

This case challenged a section of Utah law that requires, in order for the court to approve a surrogacy agreement, that “medical evidence shows that the intended mother is unable to bear a child or is unable to do so without unreasonable risk to her physical or mental health or to the unborn child.”

The crux of the Utah high court’s decision came down to the word “mother,” which, taken at its “plain reading” of the law, means female.

The Case

As described in the Utah Supreme Court opinion, the case was brought by the intended parents—a married gay couple—their would-be surrogate, and her husband, who petitioned the district court to validate their surrogacy agreement, as required by law. The court refused to approve the agreement because of the statute’s language requiring that the intended “mother” provide a medical justification for undertaking surrogacy. In practice, the language created a legal “Catch 22” for gay intended fathers such as the petitioners, identified in court documents only as N.T.B. and J.G.M.

In their appeal, the petitioners argued that the law violated the Utah Constitution’s Uniform Operation of Laws provision and the U.S. Constitution’s Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses and that the language of the law should be interpreted as gender-neutral, i.e. to substitute the word “parent” or “parents” for the word “mother.” The state of Utah filed an amicus brief in support of the argument that the law violated the U.S. Constitution and a gender-neutral reading of the law.

Ultimately, as the Supreme Court opinion describes, the district court determined that it could not say the legislature’s original intent when it passed the law was to interpret the word “mother” as gender-neutral. For that reason, the court declined to approve the surrogacy agreement because “neither of the legally married intended parents are women.”

The petitioners appealed, and the Utah appellate court referred the case directly to the state Supreme Court.

Like the lower court, the Supreme Court rejected the petitioner’s appeal to simply apply a gender-neutral reading to the law, arguing that to do so would subvert the legislature’s original intent. As the Utah high court opinion explains:

“[t]he statute was . . . written with gender specific language at a time when marriage in Utah could only be between a man and a woman.” [The applicable section of law] was adopted in 2005—ten years before the United States Supreme Court’s decision extending the constitutional right to marry to same-sex couples. At the time the law went into effect, Utah’s constitutional provision prohibiting same-sex marriage was operative and legally enforceable. The legislature therefore likely did not contemplate a reading of the statute that would allow same-sex couples to enter valid gestational agreements—a benefit the legislature expressly conditioned on marriage.

Indeed, as reported by Gay City News, if the word “parent” or “parents” were simply substituted for “mother,” a heterosexual married couple could quality for legal surrogacy simply by proving the intended father was unable to bear children. “And that would essentially override the clear legislative intent to limit different-sex couples from entering into surrogacy agreements to those in which the woman was medically unable to bear a child,” the article continues.

Having rejected the argument for a gender-neutral interpretation, the court turned to the issue of constitutionality, citing two landmark LGBT rights cases: Obergefell v. Hodges, which in 2015 legalized same-sex marriage in all 50 U.S. states (see our article on the legal aftermath); and Pavan v. Smith, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Arkansas must give same-sex parents who have children via assisted reproduction the same right to be listed on their child’s birth certificates as heterosexual parents. As we wrote about this case:

In Pavan v. Smith the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld the state’s right to discriminate by refusing to list both married lesbian moms, who conceived via assisted reproduction, on their baby’s birth certificate, instead listing only the biologically related mother.

That omission constituted unequal treatment, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2017, because heterosexual couples in Arkansas who conceived using assisted reproduction were required by law to list the husband as “father” on the child’s birth certificate. The high court’s verdict: States must issue birth certificates including the female spouses of women who give birth in the state if they include male spouses of women who give birth.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Pavan cited the earlier Obergefell decision, which prohibited states from denying same-sex couples “the constellation of benefits that the States have linked to marriage."

In its August 1 opinion, the Utah Supreme Court concluded, “Because a plain reading of [the applicable section of law] works to deny certain same-sex married couples a marital benefit freely afforded to opposite-sex married couples, we hold the statute violates the Equal protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment, under the analysis set forth in Obergefell.”

The Utah high court also ruled that the clause requiring a “mother’s” medical justification to qualify for surrogacy was “severable” and could thus be deleted entirely from the statute. The law would still serve the legislature’s intended purpose to regulate surrogacy in the state and to protect the well-being of children born via assisted reproduction, it concluded.

Although surrogacy continues to be strictly limited in Utah, the recent decision is a step forward for reproductive freedom and for LGBTQ equality in the state, at a time when some conservative jurisdictions continue to test every legal angle to dodge compliance. Ironically, as pointed out in the Gay City News’ very thorough report, Utah now enjoys a right to legal surrogacy that progressive New York has yet to win. We hope for a happy update to that story very soon.